As the operator of the world’s biggest e-commerce site, Amazon has lots of experience running huge computer systems. In 2006 it launched its cloud as a separate business. Today AWS offers hundreds of different services, from raw number-crunching and data storage to encryption and machine learning. It claims more than 1m customers, from the tiniest startups to titans like General Electric.

“THIS is the new normal,” extolled a visibly excited Andy Jassy, the boss of Amazon Web Services (AWS), as he reeled off one new service after another at a corporate bash on October 7th in Las Vegas. AWS is Amazon’s cloud-computing arm, delivering all manner of services that are hosted in data centres and delivered over the internet. The offerings highlighted by Mr Jassy included something called Snowball, a suitcase-sized box packed with 50 terabytes of digital memory, a dozen of which could hold the entire library of Congress. Firms can use the device to transfer mountains of data to AWS’s cloud in one fell swoop. Such snowballs, AWS hopes, will turn into a digital avalanche to fill up even more Amazon data centres.

How big Amazon’s cloud has become is a well-kept secret. In Las Vegas Mr Jassy said that AWS now has 50 “points of presence” (which may mean big data centres) worldwide and presented many charts showing triple-digit growth, but was silent on absolute numbers. But Amazon has recently started to release financial results for its cloud-computing business which look very promising (see chart).

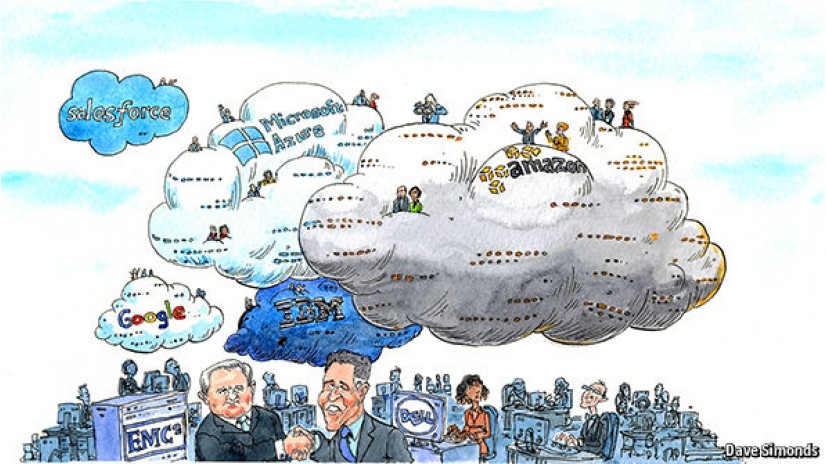

The new normal feels more threatening if you are one of the old guard. The shift to the cloud is the biggest upheaval in the IT industry since smaller, networked machines dethroned mainframe computers in the early 1990s. At the same time as Mr Jassy was tub-thumping in Nevada, Michael Dell and Joe Tucci, the chief executives of Dell and EMC, big makers of computers and digital storage devices respectively, were hammering out their own response to this changing landscape.

The agreement that they announced on October 12th, whereby Dell will acquire EMC for $67 billion, is the biggest technology deal ever, adding to a wave of mergers across many industries (see next article). It can still be called off if another suitor for EMC emerges, but that looks unlikely. Activist investment funds led by Elliott Management, which has a 2.2% stake in EMC, had been pushing the firm to boost its share price. Elliott, which stands to make a profit of more than 20% on the deal, has said it “strongly supports” the merger. Around $45 billion of debt financing, which Dell and its partner Silver Lake, a private-equity firm, need to complete the takeover, is securely in place.

The deal is not without risks, however. The big debt load is one, although Dell has been successfully paying back money it borrowed for its own 2013 buy-out. The task of integrating the two firms will be another challenge, as Meg Whitman, the boss of HP, a rival member of the tech old guard, was quick to point out.

Dell and EMC have long been cognisant of the disruption around them. Mr Dell, who founded his firm in 1984 in his college bedroom, where he built personal computers (PCs) from off-the-shelf parts, took it private in 2013: he wanted to be able to lead it through its transformation without the distractions of quarterly results and activist investors. (This transaction partly reverses that decision thanks to a bit of financial engineering involving VMware, a listed software firm in which EMC holds a large stake: as part of the deal, EMC shareholders will get about a tenth of a share of a new VMware “tracking” stock, which will be issued by Dell’s holding company.)

Mr Tucci, for his part, has shown a knack for buying firms that sell key components for cloud computing—and then leaving them alone. The most prized asset in EMC’s loose “federation” of firms is VMware, whose “virtualisation” software makes data centres more efficient by spreading work around servers.

Yet both Dell and EMC are still dependent on the businesses that first made them big. Since Dell no longer publishes financial results, it is hard to know what exactly is going on. But analysts say that despite a push into selling more corporate technology, such as servers and storage devices, Dell still relies for the majority of its revenues on PCs—a business which continues to decline as a result not just of cloud computing, but the rise of smartphones. Global PC shipments fell by nearly 8% in the third quarter, compared with the same period a year ago, according to Gartner, a research outfit.

EMC’s mainstay, digital storage devices of all kinds and related software, is still growing, but not as fast as it used to—because many firms now opt to store data in the cloud or to buy cheaper gear from competitors. Early in this decade storage sales increased by double digits annually, a rate that dropped to 2% last year. As part of the announcement of the merger, EMC released quarterly results that came in below financial analysts’ expectations.

All of which helps to explain why Messrs Dell and Tucci are keen to merge their companies. The deal, says Steven Milunovich of UBS, a bank, will strengthen Dell’s business of selling computing infrastructure to companies rather than PCs, and also gel with another development in the IT industry: converged hardware. Traditionally, servers, storage devices and networking equipment have been bought separately. Now they are being increasingly offered in integrated bundles by one vendor, sparing customers the tedious task of making them work together smoothly—a trend that has been pioneered by EMC in a joint venture with Cisco, a big maker of networking gear.

The next step, which some big cloud operators that make their own machines are already taking, is to merge the different components in basic computers and have software turn them into servers, storage devices or routers as needed. Dell, which excels at making commodity hardware, seems to hope that it will be able to sell such converged devices to firms that want to build their own “private” clouds, and perhaps even to big cloud providers, many of which now have contract manufacturers put together their hardware.

A broader question is whether the merger will trigger a flurry of other deals. The deconstruction and reconstruction of the IT industry has already begun, even if full-scale consolidation is not imminent. HP has already made the decision to split itself in two on November 1st. Earlier this year Oracle was mentioned as a potential buyer of Salesforce.com, a big provider of web-based business software.

If history is any guide, the industry’s old leaders won’t be its new ones. Of the proud mainframe companies, after all, only IBM and SAP still stand tall. Even after the merger, it is not assured that Dell will remain in the top league. So far, the only firm from the old guard that seems certain to keep a spot is Microsoft, which has managed to build a sizeable cloud business called Azure. Google, another big cloud provider, also seems likely to be among the new IT kingpins. But the biggest cloud of all belongs to Amazon—which looks ever more likely to be the new top dog of the tech pack.