Pause before fast-forward

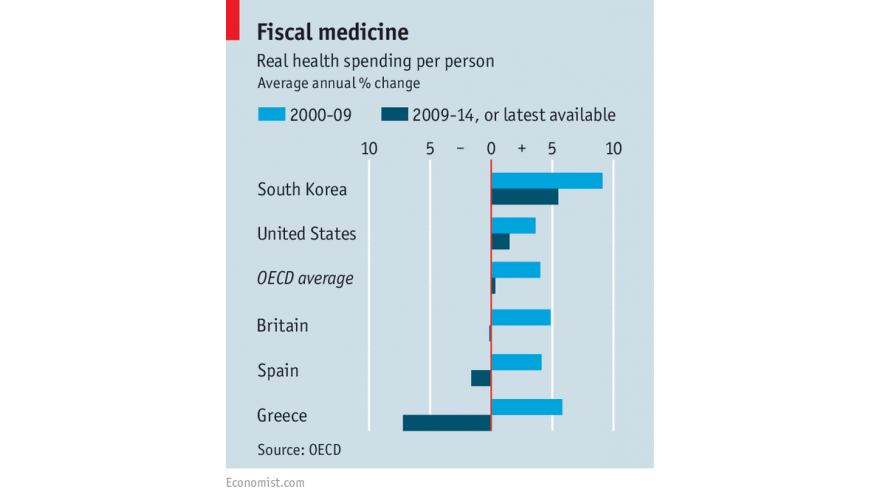

Between 2000 and 2009 real health spending per person grew at an annual rate of 4% on average across the 30 or so mainly rich countries that belong to the OECD. Since 2009 the rate has slackened to just 0.3% a year (see chart). Despite the slowdown in America, spending growth there has been higher than the OECD average. In several countries, health spending per person has fallen, most markedly in the periphery of the euro area.

The recent slowdown in American health spending has attracted much attention. Some have dared to hope that a decades-long trend has been broken, in part because of cost-saving measures within reforms introduced by Barack Obama in 2010. But a new study of international health spending and financing published by the OECD, an intergovernmental think-tank, shows that wider influences must be at work, since America is not alone in experiencing such a deceleration over the past few years. That in turn suggests that medical spending is merely pausing before resuming its upward trajectory.

The generalised nature of the slowdown in health spending indicates that it occurred mainly in response to the economic setbacks arising first from the global financial crisis and then from the euro crisis. That has induced a general squeeze on public spending, including on health care. The recession and sluggish recovery have kept wages—a big part of medical budgets—subdued, says Mark Pearson, who is in charge of health policy at the OECD.

This strongly suggests that the hiatus in health-spending growth in the rich world will prove temporary. As advanced economies continue to recover, cost pressures within health systems that are currently being suppressed will push up budgets again. The OECD projects an increase in average public health spending from 6% of GDP to 8% over the next two decades.

That rise will occur because the underlying forces pushing up medical costs remain in place. In particular health spending is driven by technological advances that increase the scope and quality of medical interventions. These improvements are hugely valued by people, reflecting the fact that as they get richer (and older) their demand for health care rises. The bill is largely picked up by third parties, whether through public budgets or by insurers in the private sector. This weakens incentives to resist rising costs.

Such are the pressures that some of the apparent success in restraining costs may prove illusory. In particular, general budget curbs can work for a time but the dam eventually bursts. In Britain, for example, there is mounting evidence that the clampdown on its health budget will be difficult to sustain. Programmes to prevent disease and to promote healthier behaviours have been particular targets for cuts across rich countries, even though this is a false economy in anything other than the short term.

Although demand can be held back by user charges or higher co-payments, this can have unwelcome effects in deterring sick people who are less well-off from getting the care they need. A more promising direction for containing costs is to overhaul the ways that providers are paid and to generate more competition between them. But these methods have limits in systems where public financing predominates. The unpalatable truth is that it is very difficult to restrain medical spending. In America as well as in other advanced countries, health expenditure will remain a fiscal headache because it is the hardest component of public spending to tame.

Comments